Table of Contents#

Introduction#

Let’s build the basic boilerplate for an OpenId Connect based Authentication mechanism for our Node.js / Typescript app that supports SSO (Single Sign On experience) out of the box and that will fit very well with a microservice architecture with no statefulness added.

This sort of setup is great for microservice architectures because

- it provides clear authentication (and authorization) interfaces based on industries best practices

- it works well with self contained auth tokens that can be used for communications across microservices

- it requires no extra stateful layers (such as session databases)

- it can be easily expanded to make up a Single Sign on experience across multiple apps and even across companies.

So what is OpenId Connect?#

OpenId Connect (a.k.a oidc) is an interoperable authentication protocol based on the OAuth 2.0 family of specifications.

The line between OpenId and OAuth is blurry in practice and in learning material in the web the concepts are sometimes a mix and match of both.

I like to think of OpenId and OAuth as a set of specifications that define standard APIs for Authentication and Authorization, respectively.

OpenID Connect lets developers authenticate their users across websites and apps without having to own and manage password files. For the app builder, it provides a secure verifiable, answer to the question: “What is the identity of the person currently using the browser or native app that is connected to me?”

This has enabled 3rd party Authentication providers and the always present “Log In with X” you see around the web, such Auth providers include Google (the one we use in the example code), Auth0, Microsoft, Okta, among many others. See certified providers here

Additionally, OpenId Connect can be used in enterprise settings like shared Auth and Identity provider across many apps (think about Microsoft active directory, or Okta’s service) providing a Single Sign On experience; and also as a way of structuring a microservice architecture with multiple “clients” (OAuth lingo for applications that interact with the Auth Server).

If you want to go down the rabbit hole and learn more check these resources out

- Nate Barbettini’s OAuth and OpenId in plain English

- Okta’s Ilustrated Guide to Oauth and OpenId Connect

- IEEE OAuth 2.0 RFC (it is dense but has all the details)

Here is a nice illustration of one of the most common ways of Authenticating with OAuth 2.0 and OpenId Connect: the authorization code flow

Source: heavily inspired by this Nate Barbettini’s presentation

That’s fine, but why should I care?#

OAuth 2.0 and oidc have become ever present in the modern application development landscape and although the tooling is really good and hides a lot of details chances are that you will still require a decent high level understanding of what you are doing.

This applies both to already existing applications and to the practice of designing and creating new applications with modern architectures such as microservice oriented one.

I will try to find the sweet spot between comprehensive and high level coverage, let’s hope I can achieve it.

Show me the code!#

Let’s build a simple application that uses OAuth 2.0 and oidc. The idea is to show

- how to use 3rd party Auth and Identity providers

- how to integrate those mechanisms with something familiar to the web platform: session cookies!

- how to easily manage sessions in the Request-Response web app cycle (no libs here!)

- how the session can be structured to be self contained for a stateless session management

- security implications

- how this application can be used to achieve SSO (single sign on experience across multiple apps)

You can check the full code here.

A note on tooling#

I have found a nice certified NodeJs library called openid-client, it is a nice library with decent Typescript support that makes it very easy to integrate Identity providers.

Another really cool thing about OpenId Connect is the concept of Discovery which

basically means that although there are a bunch of parameters involved in setting up a proper

oidc flow like multiple urls, encryption algorithms, public keys to verify tokens, etc;

you really just need to use one url and, if the client library you are using supports it, the client will

use this Discovery mechanism to look for a Discovery Document that contains all the necessary parameters

and you are good to go!. openid-client supports this!.

Step 1: What are we building?#

We are going to use a top-down approach, so first we are going to cover how the app works at the business logic level and in later steps we are going to cover the “lib” side of things where we implement the proper express middleware, session management, cookie storage, etc.

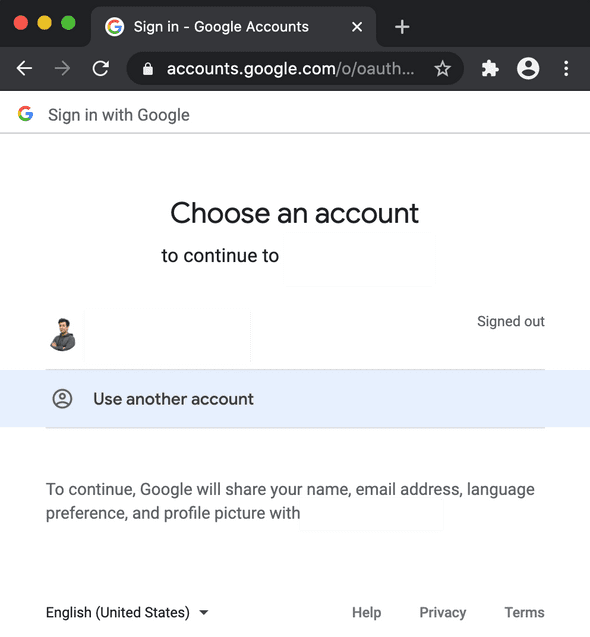

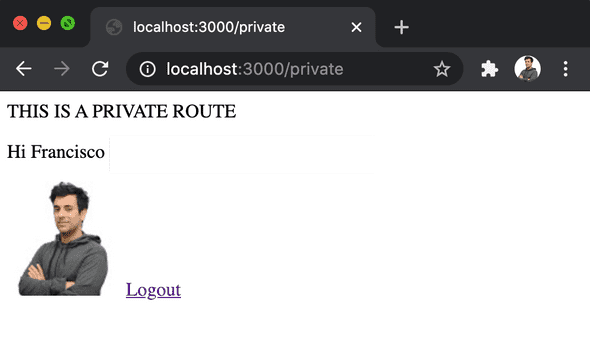

The app is really simple, it has two content routes

/or the home where we show the “login” button and it is public./privatewere we display some information about the currently logged in user. If there is no user logged in we simply display an error.

Here are some pictures:

There are at least two additional routes that have to do with the OAuth flow that we will cover later.

This is the index.ts that makes up the high level app implementation, think of this

as a mix of the boilerplate plus the two domain / business specific routes.

const app = express();

// Necessary for express to parse the cookies into a nice

// higher level object

app.use(cookieParser());

// initialises the Issuer and the Client

app.use(auth.initialize);

// Deals with the user session

app.use(auth.session);

// Adds the OAuth / OpenId necessary routes.

app.use(auth.routes());

app.get("/", (req, res) => {

// use the pre configured view engine

// to render the index.mustache file

res.render("index");

});

app.get("/private", auth.requireAuth, (req, res) => {

// This is the main high level hook for the user

// session, we will be building this later

const claims = req.session!.tokenSet.claims();

// render private.mustache and interpolate

// the following data

res.render("private", {

email: claims.email,

picture: claims.picture,

name: claims.name,

});

});

app.listen(process.env.PORT, () => {

console.log(

`Express started on port ${process.env.PORT}`

);

});Next we will cover more details (descending into the details).

Step 2: Initializing#

First we need to initialize the openid-client

Issuer (the one that discovers all the publicly available OpenId configuration) and later the Client

(the one that we will use to make all the underlying HTTP calls).

We will abstract this step into a middleware and save the instances into the req.app object

since these things need to be instantiated once per app.

export async function initialize(

req: Request,

res: Response,

next: NextFunction

) {

if (req.app.authIssuer) {

return next();

}

const googleIssuer = await Issuer.discover(

"https://accounts.google.com"

);

const client = new googleIssuer.Client({

client_id: process.env.OAUTH_CLIENT_ID!,

client_secret: process.env.OAUTH_CLIENT_SECRET!,

redirect_uris: [`${getDomain()}/auth/callback`],

response_types: ["code"],

});

req.app.authIssuer = googleIssuer;

req.app.authClient = client;

next();

}Note: getDomain is a thin helper that returns exactly this http://${process.env.HOST}:${process.env.PORT}.

Step 3: Log In#

We have a nice comprehensive sequence diagram of the all the HTTP redirects and interactions that make up the complete OAuth / OpenId Connect authorization code flow below in a bonus section

In this step we are going to build the two endpoints necessary for this type of auth flow:

- Auth entry point: Create a route that redirects to the right oidc provider authentication page and that kicks starts the whole auth flow, in our case we simply called it:

/auth/loginbut you can use whatever you like. - Callback: Create a route that the oidc provider will redirect back from the auth page with the auth code that we will later exchange for the proper access, id and refresh tokens. In our case we simply called it

/auth/callbackbut again it can be whatever you want it to be.

We also encapsulated these routes into a nice middleware that we called auth.routes.

// Auth entry point.

router.get("/auth/login", function (req, res, next) {

// Check the full code to see a

// concrete implementation of this

const state = calcState(extraContent);

// calculate the url where we want to redirect to

const authUrl = req.app.authClient.authorizationUrl({

scope: "openid email profile",

state,

});

setAuthStateCookie(res, state);

res.redirect(authUrl);

});

// Callback

router.get("/auth/callback", async (req, res, next) => {

const client = req.app.authClient;

// extract all the necessary query params

// like the authorization code.

const params = client.callbackParams(req);

// read the state cookie

const state = getAuthStateCookie(req);

// exchange the authorization code for the access,

// refresh and id token, this is what makes up the

// main `Back channel` communication, it is considered

// more secure and will include client_id and client_secret.

const tokenSet = await client.callback(

`${getDomain()}/auth/callback`,

params,

// The lib will compare the state that the

// identity provider passes as params

// with the one we stored in the cookies.

{ state }

);

// We can fetch the userinfo (basic identity attributes)

const user = await client.userinfo(tokenSet);

// Set the session cookie,

// we could also set req.session but

// since we are returning immediately is not

// a must

const sessionCookie = serialize({ tokenSet, user });

setSessionCookie(req, sessionCookie);

res.redirect("/");

});Notes:

- check the complete code to see how to implement logout and a back-to-original-route mechanism

As you can see the Auth entry point is a very simple sync redirect to the Identity provider’s login,

the library is doing a lot of the work for us but the authUrl will contain the client_id,

the callback url http://host:port/auth/callback in our case, required scopes, etc.

This is also what we call the “Front channel” and it is considered not entirely secure, that is why

we are not sending the client secret at this stage, remember that this happens all in the browser via

HTTP redirects.

The Callback will be redirected from a successful login with the Identity provider and will exchange the authorization code for the tokens (check inline comments). This is the step where we more commonly deal with persistent sessions, notice that the Identity Provider doesn’t deal with this and that’s something we need to deal with ourselves.

Check the state parameter, this acts as a sort of XSRF a.k.a. CSRF a.k.a. csurf token that we can use to

prevent XSRF attacks but also to store state across the OAuth flow. See exercise at the bottom for more info.

Check the full code for a concrete but very simple working implementation.

We are going to use a very simple self contained stateless strategy here, we will cover it in more details in the next section but at a high level what we are doing is setting a persistent cookie (the session cookie) that will travel in all requests from the browser to our local server and that we will use to identify users that already identified themselves.

Step 4: Persistent Session#

There are several ways of handling sessions but in most cases it all boils down to persisting a session across requests and identifying requests with one or zero sessions, meaning, identifying the already authenticated and identified users that are making requests to our app or simply acknowledging that there is no previously authenticated user.

Sessions are most commonly persisted in the form of a long lived cookie in the browsers and their content might be a session id that is mapped to the session object in a database server side which is the stateful solution; or the content might be the entire self contained session object, which is the stateless solution, this is a simpler approach that will work for us and that has its merits in the microservice architecture.

Why do we care about stateless vs stateful? Having a self contained cookie means that we can know certain facts about the authenticated users without having to either interact with a database or another service. Stateless is desired as much as possible because it is easy to horizontally scale i.e. adding more instances of the app running in other nodes in our cluster, whereas scaling stateful services is another whole challenge (think about master slave relationship between databases, replication, backup, consistency considerations, etc). The typical solution for a stateful session is to store a simple session id in the browser and then associate that id in a key value database such as redis

When do we write the session cookie?

We write it at two main steps:

- after login in

- after refreshing the auth tokens (not necessary in a stateful session schema)

We also clear it in two main steps:

- after logout

- after trying to refresh a token and the refresh token has expired.

And when do we read the session cookie? And what do we do with it?

This where the fun begins. We read the session cookie on every request,

and if we find one then we are going to parse it into a session object or instance

and store it in the req object, this fits super fine because the parsed, hydrated session

object only applies on a particular request, the next request might belong to another user or even

to a non authenticated user.

Why do we need to parse it? Basically, we will store it as string in the cookie and when

we read the cookie we are going to parse it back to an object, this is a very simple approach, more

commonly you will store the session as a base64 encoded json object to save space and later you will

parse it into an instance of a class so that you can cache some results and provide certain useful methods

to the rest of the app. In our case we simply reuse the TokenSet class with useful methods that

the openid-client lib provides.

This is a nice illustration of the flow you will soon see in code:

Enough talk, let’s code:

export async function session(

req: Request,

res: Response,

next: NextFunction

) {

const sessionCookie = getSessionCookie(req);

// If there is no session cookie it means there is no

// authenticated user associated with this request,

// no further work needed.

if (!sessionCookie) {

return next();

}

const client = req.app.authClient;

// Parse the cookie into a TokenSet instance

const session = deserialize(sessionCookie);

// Refresh the tokens if necessary

if (session.tokenSet.expired()) {

try {

const refreshedTokenSet = await client.refresh(

session.tokenSet

);

session.tokenSet = refreshedTokenSet;

// set the cookie with the refreshed tokens

setSessionCookie(req, serialize(session));

} catch (err) {

// this can throw when the refresh

// token has expired,

// logout completely when that happens

clearSessionCookie(req);

return next();

}

}

// We also verify that the tokens inside the cookie are valid

// with public keys mechanisms covered by the JWT spec.

// This is unfortunately a private method of the lib, but basically

// it grabs the id_token and decodes it as JWT with a public key

// that we got as part as the discovery process, if this succeeds it means

// that the token inside the cookie is a token that has been crated by our

// identity provided and thus it is secure and fine and we can trust it.

const validate = client.validateIdToken as any;

try {

await validate.call(client, session.tokenSet);

} catch (err) {

console.log("bad token signature found in auth cookie");

return next(new Error("Bad Token in Auth Cookie!"));

}

// After all that work the only thing remaining is

// to store the valid session object into req.session

// for the rest of the app to use.

req.session = session;

next();

}What might the rest of the app do with req.session?

Just to give some ideas:

- check if there is a user logged in (i.e. only allowing to view certain content to authenticated users)

- display information about the logged in user, such as menu icons etc

- fetch data associated with a user to a database or another service

- check user permissions and create a more complex allow list of routes

- many many more things.

The main point of this middleware (which is inspired by prior work such as

express-session and Passport.js) is to abstract all the logic of

parsing the session cookie, refreshing if necessary and hydrating the req.session object

in a single place, the rest of the app can rely on that being there and that nothing else will

need to be done there.

We also have a nice example middleware that prevents non authenticated users to access certain routes:

export async function requireAuth(

req: Request,

res: Response,

next: NextFunction

) {

const session = req.session;

if (!session) {

return next(new Error("unauthenticated"));

}

next();

}Of course this will only work if the session middleware runs first in the middleware chain

and this runs later, that is why it is important that your session middleware to be run as early as possible,

at least before your routes definitions.

Step 5: Log Out#

In here you have two options:

- Logging out of just your app

- Logging out entirely out of the identity provider

We are going to use the first approach:

router.get("/auth/logout", async (req, res, next) => {

const client = req.app.authClient;

const tokenSet = req.session?.tokenSet;

// Make sure the access token we got from the identity provider

// gets revoked, this is for security reasons

await client.revoke(tokenSet!.access_token!);

// Clean up session cookies

clearSessionCookie(res);

res.redirect("/");

});Step 6: Putting it all together#

With a little bit of express experience we can encapsulate all the previous logic into nice middlewares and leave the rest of the app to deal with domain / business logic.

We put all the authentication related code in the auth directory, and the high level api is

made up of middlewares. You can use middleware factories for more complex use cases (functions that accept

options and return middlewares, and yes, the router is a middleware).

Step 7: Single Sign On#

Single Sign On (SSO) means that if you are already authenticated with one app using the same OpenId Identity Provider then you will be almost automatically authenticated we other apps.

We have set a nice example in the repo, check instructions to see it in action here.

How does it work?

- the Session cookie is completely independent in each app (see the domain note on the repo’s README).

- If you already logged in with app1 then when you try to login with app2 then you won’t need to introduce your credentials and the OAuth flow will happen without you (the user) needing to do anything, that is why I say it is almost automatic.

Bonus: the complete sequence diagram of oidc authentication#

Most of the time you will see this sequence diagram simplified, but I wanted to show you in full details all the steps and http redirects there are inside this transaction, most of the time you won’t need to worry about these but I think it is a nice exercise to have it detailed fully like this:

Bonus: what are the access, refresh and id tokens?#

Each identity provider might use them differently but these are some of the core ideas behind each of them

- access token: an opaque value with a short expiration that the identity server uses to identify a user (think of it as a portable session id)

- refresh token: another opaque value with a longer expiration that it is used to refresh the access token and the id token. Long lived sessions are typically handled by this two step process to give more control to identity providers.

- id token: this is what OpendId Connect adds, this is a self contained jwt that contains claims (attributes) about the identity of the currently logged in user. This is what makes sense the most to use inside your own system to check the identity of the user. You can cryptographically verify its validity and it will contain minimal information such as the

subid (the subject id or the user id), the email, the names, etc.

Exercise 1#

How would you implement a “back to” functionality?

Let’s say that you originally tried to access /private/route/1 but you weren’t authenticated yet

so we redirected you to /auth/login.

After going through all the auth flow we would like for the app to redirect automatically back

to /private/route/1.

Show me the answer

See answer here. A couple of notes:

- you basically store a

backToparam in the state and in the cookie - you can store more stuff in the

state - we need it also in the cookie to prevent XSRF.

- Check the IETF standard and read more here

Closing#

Did you like the content? Consider sharing it in your social circle and subscribing to receive awesome exclusive content right into your email box.